MERS Outbreak

Bats and Coronaviruses

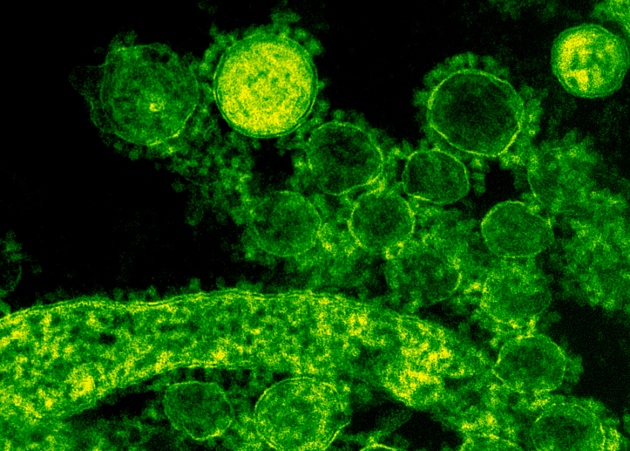

The outbreak of MERS in South Korea has been making the news lately. You might be more familiar with the SARS outbreak of 2002-2004, so I will start there. SARS stands for, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, and is a disease caused by the SARS coronavirus. Viruses are microscopic protein shells of RNA or DNA nucleic acid, similar to the DNA that programs your own cells, except on a smaller scale. Viruses infect cells, and divert life-sustaining machinery to make more copies of the virus, often killing or harming the host cell in this process.

Coronaviruses can infect mice, pigs, humans, chickens, dogs, bats, camels (and many other animals). I list camels and bats last because it is believed that naturally occurring mutations in these coronaviruses allow them to jump from bats, in the case of SARS, and camels, in the case of MERS, to humans.

But what are the origins of these pesky coronaviruses? Where did the bats and camels get them? Nucleic acid DNA-RNA sequencing allowed scientists to trace both MERS and SARS back to bats, and both have likely been co-evolving with bats for thousands, if not millions of years, as viruses are believed to pre-date cellular life itself (Holmes, E.C. 2011).

Should we be worried about SARS and MERS? Yes, and no. Even though I am a trained microbiologist, I am more concerned about the destruction of natural habitats, which cause more human exposure to the exotic viruses these bats naturally carry. Bats have an important role in balanced ecosystems, keeping insect populations such as moths and mosquitoes under control, as well as plant pollination, such as the saguaro cactus. Therefore, we cannot just start spraying their cave homes with poison to eradicate the virus reservoir.

Solutions

As MERS and SARS infections have a frighteningly high case-mortality rate of 60% (World Health Organization), the fast, easy, and dirty solution is to quarantine, and treat infected patients with broad-spectrum antivirals. These antivirals activate an interferon response, which is what white blood cells naturally secret to deal with viral invaders, except these medicines activate a quicker, more robust response, hopefully helping white blood cells inactivate the virus before it kills the patient. Often, these antivirals have harsh side-effects, as any robust activation of the immune system does, such as fever and fatigue. However, these nasty effects are temporary, while death is not.

Nonetheless, there are sustainable solutions to an undoubtable future of increasing, exotic, viral outbreaks, due to bat and other zoonotic reservoir systems: animals with the ability to transfer viruses naturally circulating amongst their populations, which minorly affect them, to humans, who are more detrimentally affected. This solution would be to preserve natural barriers, limit unnecessary contact, and preserve harsh medications for the last-line of defense. Destruction of bat habitats have led to more sightings of bats at unusual times of day, when they should normally be sleeping, as well as more human contact, leading to increased chances of viral transmission. Bats also transmit the rabies virus, which luckily, there is also a vaccine for, which has saved many from an Old Yeller or Their Eyes Were Watching God fate. This is a win-win for bats and humans.

Canadians can find more information with Environment Canada, petition representatives to fund habitat restoration projects, and start their own independent grass-root campaigns to keep their cities and towns sustainable.

Americans can find more information with NOAA Habitat Conservation, petition representatives to fund restoration projects, and start their own independent grass-root campaigns to keep their cities and towns sustainable.

An international restoration ecology program includes the World Health Organization Vector Ecology Management (VEM).

For further reading, check out Integrating Ecology and Poverty Reduction: Ecological Dimensions by DeClerck, F. 2012.